Por: Luis Espinosa Goded

Fuente foto WSJ.

Deirdre McCloskey es,

en mi opinión, la mejor economista viva -de seguro desde que falleció Leonor

Ostrom-, y uno de los cinco mejores economistas -de ambos géneros- vivos. Por

eso cada vez que Deirdre McCloskey publica algo es para mí un placer

intelectual, pues sé que pasaré unas horas deliciosas leyendo su prosa

efectista y sus ideas originales. Pues una de las múltiples cualidades que

hacen que sobresalga Deirdre sobre los demás economistas es el estilo de su

escritura. Será que es hija de una poeta, será que una de sus primeras

contribuciónes significativas a la economía fue en el campo de la retórica

económica (The rethoric of economics),

sea por lo que fuere, su estilo de escritura es vibrante, entretenido,

impactante. Leerla es un placer.

En esta ocasión se suma polémica a la alegría

pues

Deirdre McCloskey ha escrito una reseña (que será publicada en el Erasmus Journal of Philosophy and Economics) de 55 páginas del afamado libro de Thomas Piketty "Capital in the XXI century" , el libro que se supone que ha vuelto a actualizar el problema de la desigualdad, haciendo un prolijo análisis de la cuestión de los ingresos por capital y trabajo en los últimos siglos. Lo primero que señala Deirdre es que lo más soprendente del trabajo de Piketty es su influencia, el que un libro de teoría económica/clionometría se convierta en un super-ventas... aunque no en un súper-lecturas:

Deirdre McCloskey ha escrito una reseña (que será publicada en el Erasmus Journal of Philosophy and Economics) de 55 páginas del afamado libro de Thomas Piketty "Capital in the XXI century" , el libro que se supone que ha vuelto a actualizar el problema de la desigualdad, haciendo un prolijo análisis de la cuestión de los ingresos por capital y trabajo en los últimos siglos. Lo primero que señala Deirdre es que lo más soprendente del trabajo de Piketty es su influencia, el que un libro de teoría económica/clionometría se convierta en un super-ventas... aunque no en un súper-lecturas:

The Kindle company from Amazon keeps track of the last page ofyour

highlighting in a downloaded book (you didn’t know that, did you?). Using the

fact, the mathematician Jordan Ellenberg reckons that the average reader of the

655 pages of text and footnotes of Capital in the Twenty-First Century stops

somewhere a little past page 26, where thehighlighting stops, about the end of

the Introduction.[2.4 percent]

Las sociedades occidentales parecen estar

ansiosas de consumir (entiéndase la

paradoja) argumentos anticapitalistas. La tesis principal de Piketty es que la

desigualdad ha aumentado en los últimos dos siglos ya que la rentabiliad del

capital es superior al crecimiento de la economía, por lo que los que poseen

capital aumentan más que proporcionalmente su riqueza. Y esto parece justificar

un cambio radical del sistema económico/social en el que vivimos basado en las

críticas marxistas. Un cambio que apoyan millones de personas -y muchos

economistas- a través de movimientos como el del 99% (entiéndase

en contraposición al 1% que posee el 20% de la riqueza).

Una visión negativa del sistema económico que

tan sólo se centra en la desproporción de crecimiento entre unos y otros,

hablando de "clases estáticas" (un error de base de Marx tan

repetido, las "clases" son por definición muy porosas, son las

"castas" las que son infranqueables).

Y es que los economistas parecen preocuparse

constantemente por problemas que son más o menos reales, pero nunca parecen pararse

a reconocer el crecimiento económico que el Liberalismo (no el capitalismo

según Dierdre: "The modern world was

not caused by “capitalism,” which is ancient and ubiquitous—quite unlike

liberalism, which was in 1776 revolutionary") ha proporcionado, y que

es la verdad más maravillosa de la historia económica de la humanidad: We are gigantically richer in body and

spirit than we were two centuries ago, o que:

since 1800 in the average rich country the income

of the workers per person increased by a factor of about 30 (2,900 percent, if

you please) and in even in the world as a whole, including the still poor

countries, by a factor of 10 (900 percent), while the rate of return to

physical capital stagnated.

Sin embargo las izquierdas (o los economistas),

llevan los dos últimos siglos (desde el reverendo -y cenizo- Malthus) diciendo

que el sistema tiene graves problemas:

Then the economists, many on the left but some on the right, in

quick succession 1880 to the present—at the same time that trade-tested

betterment was driving real wages up and up and up—commenced worrying about, to

name a few of the grounds for pessimisms they discerned concerning

”capitalism”: greed, alienation, racial impurity, workers’ lack of bargaining

strength, women working, workers’ bad taste in consumption, immigration of

lesser breeds, monopoly, unemployment, business cycles, increasing returns, externalities,

under-consumption, monopolistic competition, separation of ownership from

control, lack of planning, post-War stagnation, investment spillovers,

unbalanced growth, dual labor markets, capital insufficiency (William Easterly

calls it “capital fundamentalism”), peasant irrationality, capital-market imperfections,

public choice, missing markets, informational asymmetry, third-world exploitation,

advertising, regulatory capture, free riding, low-level traps, middle-level

traps, path dependency, lack of competitiveness, consumerism, consumption

externalities, irrationality, hyperbolic discounting, too big to fail, environmental

degradation, underpaying of care, overpayment of CEOs, slower growth, and more.

Este pesimismo, este tan sólo centrarse en

supuestos problemas (casi todos ellos ya se han mostrado como falsos

problemas), es el propio de la izquierda, que Deirdre describe como algo

parecido a una patogenia adolescente mal curada que se basa siempre en la falacia de la utopía:

One begins to suspect that the typical leftist—most of the graver

worries have come from thereabouts, naturally, though not so very naturally

considering the great payoff of “capitalism” for the working class—starts with

a root conviction that capitalism is seriously defective. The conviction is

acquired at age 16 years when the proto-leftist discovers poverty but has no

intellectual tools to understand its source.

Y es que el argumento de todo el libro de

Piketty, que se remonta a Aristóteles tanto como a Marx (The most hated sort [of increasing their money], ...is usury, which makes a gain out of money

itself.), en el fondo es tremendamente simple, aunque se complique mucho

con las correlaciones y los argumentos econométricos:

The argument is, you see, very old, and very simple. Piketty

ornaments it a bit with some portentous accounting about capital-output ratios

and the like, producing his central inequality about inequality: so long as r

> g, where r is the return on capital and g is the growth rate of the

economy, we are doomed to ever increasing rewards to rich capitalists while the

rest of us poor suckers fall relatively behind.

El

problema, es, como nos dice Deirdre, que Piketty no entiende el funcionamiento

de la economía real con oferta y demanda, y no comprende la historia -que no le

da la razón a pesar de todo el aparato cliométrico que utiliza-:

The fundamental technical problem in the

book, however, is that Piketty the

economistdoes not understand supply responses. In keeping with his position

as a man of the left, he has a vague and confused idea about how markets work,

and especially about how supply responds to higher prices. If he wants to offer

pessimistic conclusions concerning “a market economy based on private property,

if left to itself” (p. 571), he had better know what elementary economics,

agreed to by all who have studied it enough to understand what it is saying,

does in fact say how a market economy based on private property behaves when

left to itself.

Piketty,

it would seem, has not read with understanding the theory of supply and demand

that he disparages, such as

Smith (one sneering remark on p. 9), Say (ditto, mentioned in a footnote with

Smith as optimistic), Bastiat (no mention), Walras (no mention), Menger (no mention),

Marshall (no mention), Mises (no mention), Hayek (one footnote citation on

another matter), Friedman (pp. 548-549, but only on monetarism, not the price

system). He is in short not qualified to sneer at self-regulated markets (for

example on p. 572), because he has no idea how they work

Como

muestra Deirdre, los errores de Piketty, como siempre en teoría económica, se

basan en no haber leído a autores fundamentales del pensamiento económico (en

este caso parece a todos los autores del "lado de la demanda"), o no

haber entendido los fundamentos básicos del funcionamiento económico.

Pero

como continúa McCloskey: Beyond technical

matters in economics, the fundamental ethical problem in the book, is that

Piketty has not reflected on why inequality by itself would be bad. Y lo

que es peor, no se fija en la riqueza creada, en los miles de millones de seres

humanos que han pasado a tener una vida mucho mejor gracias al capitalismo, si

no en la pobreza relativa, de

algunos de ellos. Esta obsesión por la pobreza relativa, por la envidia, nos

vuelve a remitir a la izquierda como un problema de adolescencia, que señalaba

Deirdre (His worry, in other words, is

purely about difference, about the Gini coefficient, about a vague feeling of

envy raised to a theoretical and ethical proposition).

A

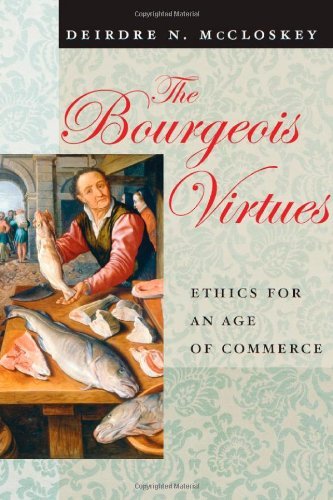

partir de aquí Deirdre dedica las últimas 20 páginas de la reseña a explicar la

tesis por la que muchos la admiramos tanto (y por la que yo creo que pasará a

un lugar de honor en la historia del pensamiento económico tras desarrollarlo en

una obra de cinco tomos): que son las virtudes

burguesas y el relato de celebración de las mismas las

que producen la prosperidad de las sociedades:

The original and sustaining causes of the

modern world, I would argue contrary to Piketty’s sneers at the bourgeois

virtues, were indeed ethical, not material. They were the widening adoption of two mere ideas, the new and liberal

economic idea of liberty for ordinary people and the new and democratic social

idea of dignity for them. The two linked and preposterous ethical ideas—the

single word for them is “equality” of respect and before the law—led to a

paroxysm of betterment.

Y

por eso Deirdre nos anima a participar y proporcionar la prosperidad, no sólo a

clamar contra la pobreza:

Remarks such as “there are still poor people”

or “some people have more power than others,” though claiming the moral

high-ground for the speaker, are not deep or clever. Repeating them, or nodding

wisely at their repetition, or buying Piketty’s book to display on your coffee

table, does not make you a good person. You are a good person if you actually help

the poor. Open a business. Arrange mortgages that poor people can afford.

Invent a new battery...

Pero

no nos animemos a cambiar todos el sistema económico en nombre de una supuesta

mejora de los más pobres, o en nombre de la movilidad social, pues la verdad es

que es este sistema económico del

capitalismo, el que ha producido la mayor mejora de los pobres de toda la

historia, y la mayor movilidad social:

82% of children of the bottom 20% in 1969 had

[real] incomes in 2000 that were higher than what their parents had in 1969.

The median [real] income of those children of the poor of 1969 was double that

of their parents [Isaacs 2007, quoted in Horwitz 2013, p. 7., citado en McCloskey

2014]

Y

es que la medición y la discusión sobre la pobreza suele estar completamente

errada, ya que se centra en la obsesión de Piketty y de toda la izquierda: La

supuesta desigualdad. En lugar de centrarse en el problema real: La pobreza.

Much of the research on the economics of

inequality stumbles on this simple ethical point, focusing on measures of

relative inequality such as the Gini coefficient or the share of the top 1

percent rather than on measures of the absolute welfare of the poor, focusing

on inequality rather than poverty, having elided the two

Pero

como señala McCloskey, la riqueza sí que ha tenido lugar en estos dos siglos

desde la revolución industrial, y es la creación de riqueza (no su

distribución) la que está acabando con la pobreza

The most fundamental problem in Piketty’s

book, then, is that the main event of the past two centuries was not the second

moment, the distribution of income on which he focuses, but its first moment,

the Great Enrichment of the average individual on the planet by a factor of 10 and

in rich countries by a factor of 30 or more. The greatly enriched world cannot

be explained by the accumulation of capital—as to the contrary economists have

argued from Adam Smith through Karl Marx to Thomas Piketty, and as the very

name “capitalism” implies. Our riches were

not made by piling brick upon brick, bachelor’s degree upon bachelor’s degree,

bank balance upon bank balance, but by piling idea upon idea.

Siendo

la idea principal "el acuerdo de la burguesía":

It’s the Bourgeois Deal: “You accord to me, a

bourgeois projector, the liberty and dignity to try out my schemes in a

voluntary market, and let me keep the profits, if I get any, in the first

act—though I accept, reluctantly, that others will compete with me in the

second. In exchange, in the third act of a new, positive-sum drama, the

bourgeois betterment provided by me (and by those pesky, low-quality,

price-spoiling competitors) will make you all rich.” And it did.

Y

es que "la pobreza es un problema

intelectual" como repite una y otra vez mi maestro Huerta de Soto, es

un problema de erróneas ideas económicas -aquellas que defiende Piketty- y que

nuestra sociedad está deseando consumir (para

auto-culparse con un síndrome algo

sádico diría), las idea de que hace falta un cambio de sistema no para ir a

mayor capitalismo, si no para ir a un mayor estatismo, exactamente lo contraio

de lo que nos ha traído la prosperidad.

Por

eso es importante combatir la miseria en el terreno de las ideas, reconociendo

y celebrando a aquellos que han hecho posible nuestro enriquecimiento, el

enriquecimiento de los más pobres: la burguesía y las virtudes burguesas. Es la

creación de riqueza la que combate la pobreza, no la redistribución como señala

Piketty. Como dice Deirdre McCloskey: Two-and-a-half cheers for the new dominance since

1800 of a bourgeois ideology and the spreading acceptance of the Bourgeois Deal.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario

Escribe tu comentario